In today’s workplace the ability and willingness of staff to voice ideas or concerns is rightly regarded as critical, both for employees and organisations.

But while the principle is widely accepted, reality is still falling short.

The Banking Standards Board (BSB) Speaking up and Listening survey researched over 70,000 employees across 26 UK banks and building societies and found that one quarter of employees with concerns don’t raise them.

To address this, more is required than just good intentions. A breezy declaration from the boss that 'My door is always open' is not enough to change a culture. Organisations wishing to engender real change need to take more targeted action.

That begins with understanding what speaking up really means within the organisational environment, and what obstacles can, often unintentionally, be put in its way.

Speaking up should be seen as a constructive act and not simply as the airing of a grievance or frustration. The employee who speaks up is often motivated by a genuine desire for change.

When considering whether it is worthwhile, the employee may crudely estimate the likelihood of the information leading to constructive change. In deciding to speak up, employees typically go through a process of weighing up relative costs and benefits. Is it safe for me to speak up? Is it worth it and will it make a difference?

Studies show that the risks of speaking up are often felt as both personal and immediate; reputational damage, disrupted relationships, negative career consequences or suffering personal retaliation.

Employees are often mindful of past experiences in which their input (or indeed the input of others) has been unheard or ignored. BSB research in 2017 found examples of employees raising concerns but hearing nothing in response or questioning decisions which were then pushed through regardless. So, when put into balance, the perceived risks of speaking up can seem immediate and clear, while the potential benefits can seem distant and unclear. So, the employee decides to ‘play it safe’ and keep silent.

A successful strategy for fostering a culture of speaking up will therefore change the experiences which cause employees to feel personally threatened and view their chances of success as low.

We suggest 4 questions that organisations and leaders may wish to ask to help them do just this

Question 1:

What do your employees currently find it easy or difficult to speak up about? Employees may think very differently about the potential benefits or risks of speaking up depending on the subject or concern they want to raise.

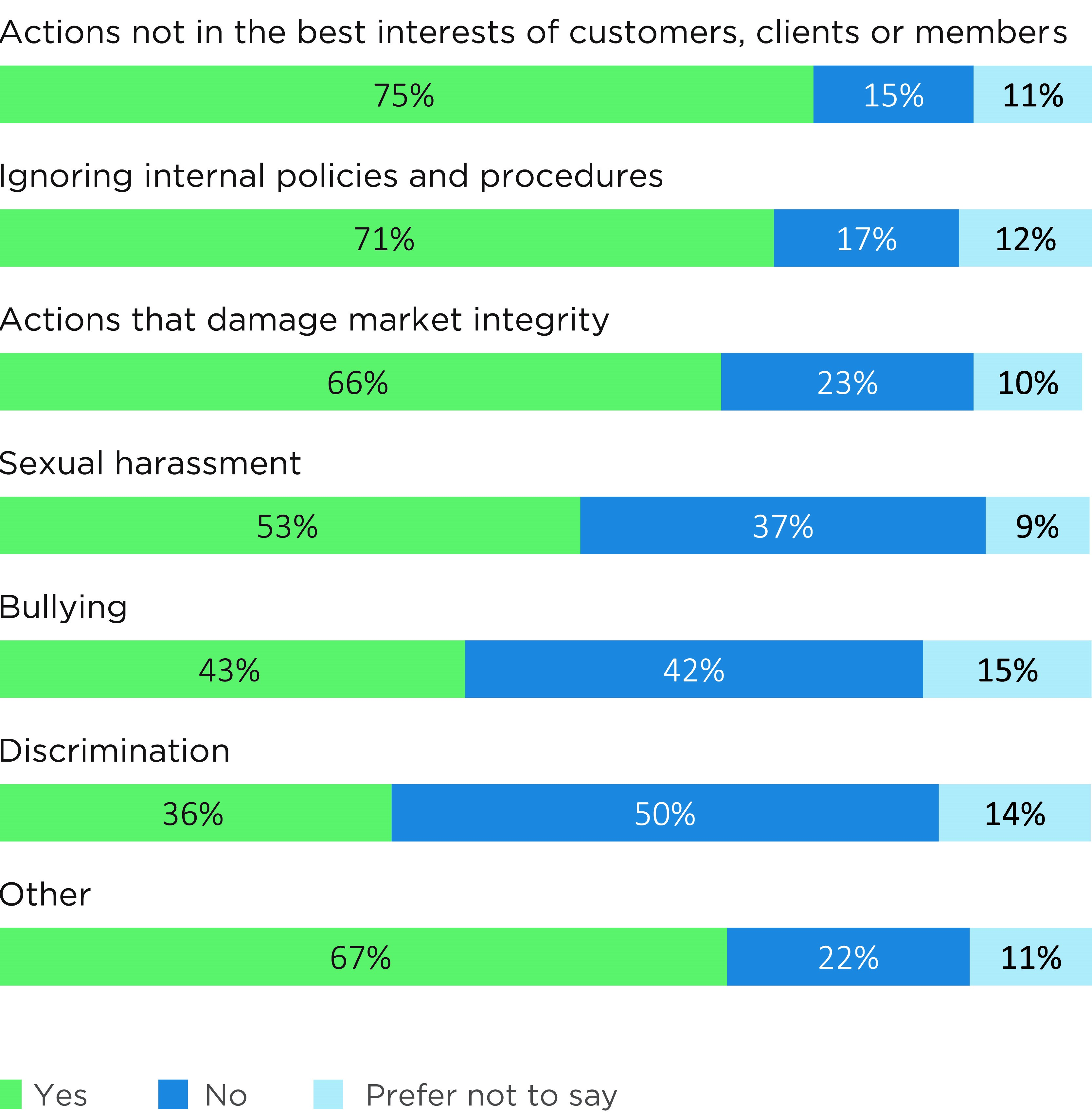

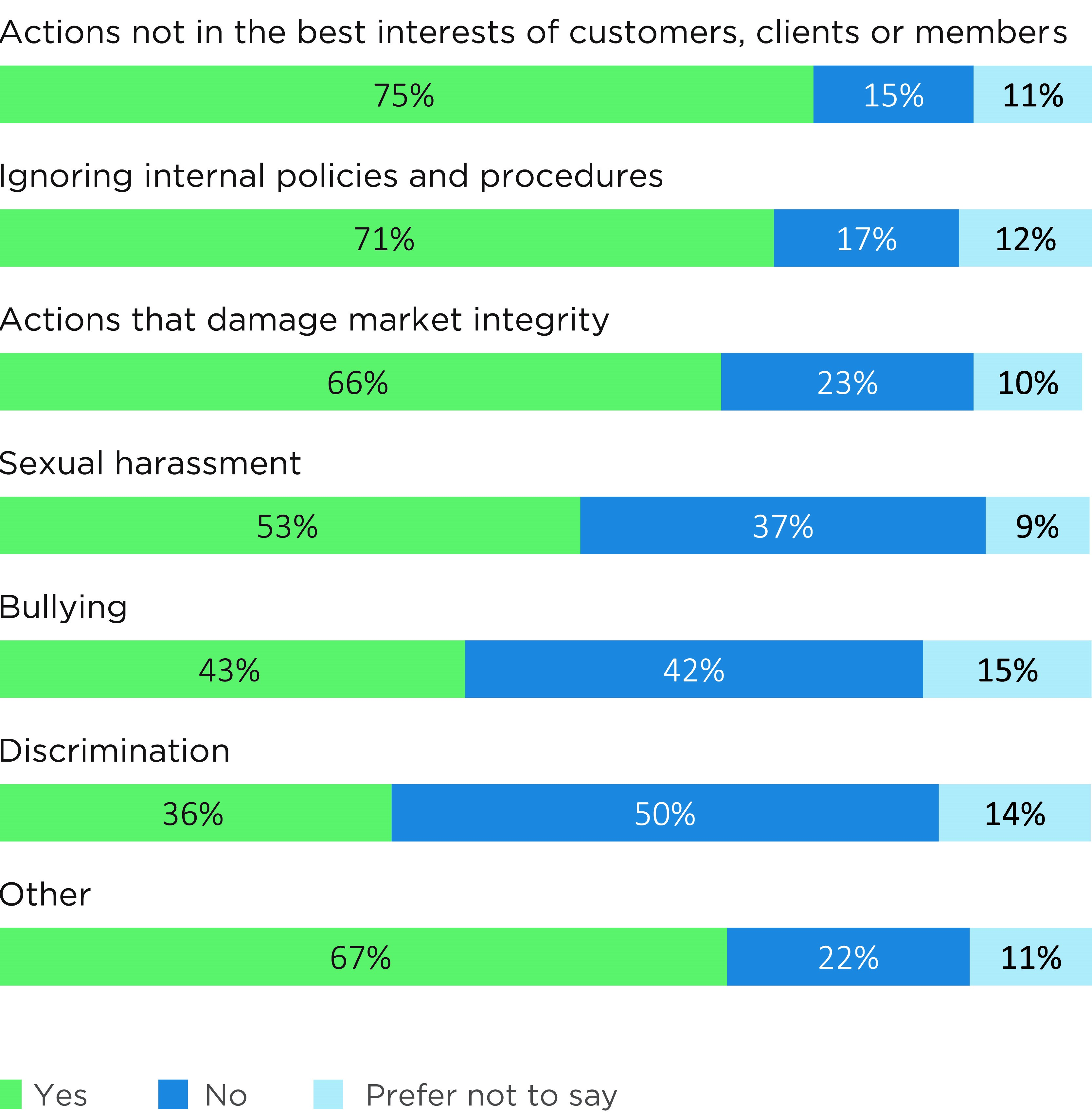

The BSB survey (2018) found that employees are more likely to come forward with concerns related to the organisation (treatment of customers, policies and market integrity) than they are with personal concerns (sexual harassment, bullying and discrimination).

Percentage of those with a concern in the past 12 months who spoke up:

Here, the focus of our attention should be on the dark blue segments in the chart – employees who had a concern they wanted to raise, but kept silent, for some reason. Why did they not speak up?

In the case of organisational concerns, the employees who didn’t come forward cited futility as the principal reason. In other words, they did not think their speaking up would lead to any action or change. Here the challenge for the organisation is to demonstrate to employees, convincingly, that their input is given due consideration and can visibly lead to change.

In the case of personal concerns, the reasons most commonly given for not speaking up are fear that it will make them look bad or will be held against them. Here, the challenge for the organisation is to foster positive team relations where employees feel that voicing personal concerns is not just individually acceptable, but a social norm.

There is no “one size fits all” solution because the barriers to speaking up vary according to the nature of the concern. Getting someone to speak up about market integrity requires a different approach to encouraging someone to come forward with a concern about sexual harassment. Narrowing the problem statement is the first step to designing an intervention that addresses the right inhibitor.

Question 2:

Who do you need to target to change the culture?

Having thought about the what, now it is time for the who. Should the intervention target the speaker themselves or the listener?

Most interventions target the speaker. Assertiveness training in healthcare professionals for example, has been shown to increase the likelihood that nurses will raise concerns about patient safety. However, discussions held at the FCA CultureSprint (in December 2018) identified that it is the listener who ultimately rewards or penalises the behaviour of speaking up. This suggests that the response of the listener is a critical lever.

BSB data shows very different patterns of listening, even within different business units of the same firm, when it comes to both employees’ expectations and their experiences of feeling listened to.

In some business units or teams, employees have a very low expectation of being listened to, in others they have high expectations that their concerns will be taken seriously and acted upon.

Similarly, their actual experience has been shown to differ. In some situations, employees find their concerns are not listened to, but in others they are listened to and make a difference.

This means that expectation and experience do not always align. In our survey we found some stark contrasts between expectations and reality.

There were business units where employees did not expect to be listened to, but those who did speak up actually found they were taken seriously and their views led to real change. In this situation, the target of a ‘speak up’ strategy should be to demonstrate that employees who actually spoke up were listened to.

Conversely, we found units where employees expected their concerns to be taken seriously, but those who did speak up found that in practice they were not listened to and their speaking up had little effect. In this situation, the target for the intervention should be the listeners and the internal channels through which feedback is given and concerns are addressed.

Understanding the past experiences of the target population is crucial in deciding where to target your ‘speaking up’ strategy.

Question 3:

How do you want your employees to be able to speak up?

There are many different ways in which employees express concerns or share suggestions and there is good evidence that employees do make strategic decisions about who they speak to and how. This is because the perceived risks and the benefits of speaking up are closely dependent on who is spoken to.

The most obvious difference is between the way employees raise a concern when speaking to a colleague compared to the way they raise the same concerns with a manager.

One field study on the consequences of influence tactics found that when speaking to their colleagues, employees are more likely to use personal appeal of friendship and loyalty or by pointing out an inconsistency with the organisation’s policies and procedures.

But when communicating to managers, employees rely more on ‘rational’ persuasion, using logical arguments and factual evidence in order to persuade the manager that their concern is relevant to meeting task objectives.

Employees sometimes hold back from speaking up to managers when they feel they lack an adequate logical explanation. Rightly or wrongly, they may believe that their input is not welcome unless they have fully developed arguments at the ready.

But there is proven value in employees coming forward with a concern based on an imprecise assessment or even a ‘gut feeling’.

One healthcare intervention has successfully targeted the ability to speak up by changing the instructions surgeons use to introduce training sessions. Trainees who were told that “Everyone is human and can make mistakes. Your opinion is important so speak up if something doesn’t seem right to you”, were significantly more likely to question the head surgeon when deliberately instructed to perform a procedure incorrectly, compared to those who heard the traditional set of instructions “Follow my instructions and save your questions for later”.

In this case, a small change in language at the beginning of a task fundamentally altered the behaviour of the team during surgery.

Enabling the trainees to express their doubts to a senior figure when feeling uncertain led to a demonstrable improvement in surgical error rates. Furthermore, it encouraged a culture in which the norm is for concerns to be raised and addressed pre-emptively.

Visualising to whom and how employees are likely to speak up in a specific context is crucial in designing a ‘speaking up’ intervention.

It will also inform how data is collected and the outcomes are measured.

Question 4:

How will you know what you are doing is working?

A variety of academically validated scales are available to measure speaking up behaviour and employee perceptions about the safety and efficacy of speaking.

Effects can be captured by taking a baseline measure in the target population prior to the intervention starting, and then again at the end.

The act of speaking up can be measured using a scale which asks participants to estimate how often they spoke up in the previous month. This scale can also be used in a peer review format, asking colleagues or managers to rate how willing a colleague is to speak up.

A 6-item academically validated scale measuring perceptions of the safety and effectiveness of speaking up is available. If the focus is psychological safety (shared beliefs about interpersonal risk taking within teams), then Amy Edmondson’s 7-item scale can be used.

Real time behavioural measures can be used in settings such as team meetings, by getting a coder to observe a group discussion and count each time an individual mentions a unique piece of information.

If the intervention is running over an extended time-period, then an organisation can simply use its existing internal reporting records to measure success, or if such a system is not in place then staff can be surveyed to ask whether they have had a concern over the previous weeks and then whether they actually spoke up about it.

Lasting change

There is no magic bullet that will change the speak up culture of an organisation overnight. But recognising that the employee’s decision to come forward is contingent on the subject, target and channel of communication is an important first step.

Breaking the process down in this way can help to change the working environment so that it provides long term consistency in its approach to speaking up and listening. Starting small and proceeding systematically can turn good intentions into real and lasting cultural change.