What you may not know about Daniel Kahneman’s 2002 Nobel prize is that he shared it with Vernon Smith, one of the first economists to use laboratory experiments. The pair played a key role in overcoming resistance to lab experimentation in their field and so played a key role in the rise of behavioural economics.

But despite these eminent pioneers, policymakers and practitioners looking to test consumer behaviour have often ignored this versatile tool.

Thanks to online labs and the widening scope for experimentation, this is now changing.

The Behavioural Insights Team (BIT), has already used online experiments to support over 65 projects, helping evaluate policy initiatives in areas such as gender equality, international development, and consumer protection.

The UK’s financial regulator (FCA) also conducts online experiments and has used the technique to investigate questions such as insurance add-on sales and algorithmic investment advice.

In this article, we give you a quick tour of the what and why of online (laboratory) experiments, as well as our reflections on the future for this methodology. If you’re hungry for more, the FCA just published a hands-on practitioners guide to running effective online experiments.

What is an online experiment?

An online experiment is a form of Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT), meaning that people are randomly assigned to treatment and control groups.

Confusingly, the term ‘RCT’ is often used to describe field experiments, where real people make real decisions in the real world. By contrast, online experiments are RCTs that simulate real decisions with recruited participants.

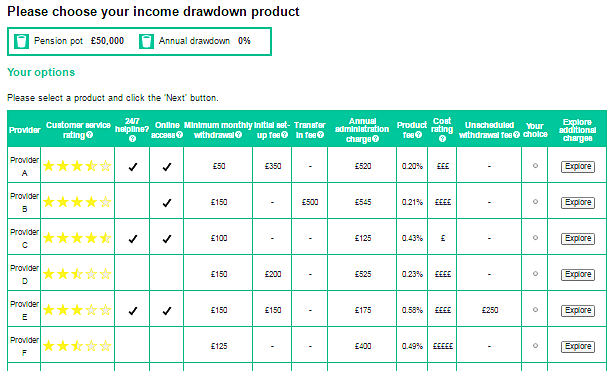

Online experiments focus on measuring choices that are predictive of real-world behaviour or the mechanisms underlying behaviour (such as trust or comprehension). The screenshot below shows an example of an online experiment simulating a price-comparison website for pension products.

Source: Oxera and the Nuffield Centre for Experimental Social Sciences (2017)

Why run online experiments?

- Greater flexibility: Experiments are used to establish whether a specific part of the choice environment, such as customer service ratings, has an impact on an outcome we care about, such as the products that consumers choose. Unfortunately, running experiments in the field can be difficult logistically and certain interventions may not be possible for ethical or practical reasons. The online lab gets around these constraints, because the researcher has complete ownership over how the decision environment is designed and what materials people see.

- Speed: With the right infrastructure, lab experiments are straightforward to set up and run, especially when they are conducted with samples of online participants. This allows data to be collected within days or weeks, which allows for more ideas to be tested and so can support evidence-based decision making when timelines are tight.

- More data: A big advantage of the lab is that it allows more (and sometimes better) data to be collected compared to other methods. For example, when BIT studied credit card repayment decisions in the lab, the experiment measured not only what people chose to repay, but also tested how well they understood what level of repayment minimised their interest payments. It turned out that many people wrongly believed that the default ‘minimum payment’ amount was the best payment to minimise their cost of borrowing. Such insights into people’s comprehension and beliefs are crucial in understanding why they make certain choices.

Online experiments are commonly used for studying tasks that people accomplish in one sitting, such as responding to an email, compiling a shortlist of job candidates, buying a flight online or checking bank balance on their phone.

Such experiments can be used by themselves, or in the exploratory and prototyping phases of a field experiment. In the latter case, we might use experiments to disentangle different behavioural mechanisms or to compare the impact of different types of communications on behaviour.

What does the future hold for the lab?

Despite a rich history in the social sciences, online experiments have only just begun to support policymakers and practitioners in solution design and evaluation. With more aspects of people’s lives moving online, there are many reasons to be optimistic about the future of the online lab. Here are two trends we see as particularly valuable:

- Better targeting: More and more of our decisions happen in an online space, and individuals are increasingly likely to have constant access to the web via mobile devices. This creates more opportunities for online experiments to reach larger, as well as more targeted audiences. In addition, it creates opportunities for organisations to recruit their own customers into an online lab. For example, some fintech companies pre-test novel changes to their interface via simulations with their own customers. Such data could be used in combination with other tools, such as data science techniques, to further enhance predictive accuracy.

- Extending to more complex decision problems: In most online experiments, respondents make their decisions individually and the simulation lasts for a short amount of time (typically about 10-15 minutes). With increased access to potential participants, new types of experiments become possible. For example, individuals can be prompted to make decisions over different periods, which can be used to study how choices change over time. In addition, individuals can be connected to others in real time, which makes it possible to study new decision problems, such as social cohesion.

The value of online experiments is already very clear, but this is still only the beginning. Their significance the benefits they can bring to policy-makers and practitioners in industry is only set to grow.

This article grew out of our shared interest in using online labs for evidence-based policy. Janna is Head of Product for Predictiv, the online laboratory platform of BIT, and Jeroen is a behavioural economist at the Financial Conduct Authority and guest lecturer in behavioural science at the London School of Economics. He recently published an FCA paper 'Using online experiments for behaviourally informed policy'.