In trying to get to grips with culture I was reminded of a seminar I attended in the 1990s led by John Adair - then visiting professor of Leadership at the University of Exeter.

Early in the session John asked the group, ‘what one word sums up leadership’. We pondered it for most of the afternoon without coming close and in the end John said: ‘The word is influence. If you can’t influence others you cannot lead.’

Twenty odd years later I found this moment coming back to me as I thought about culture. If influence encapsulates leadership, what word best sums up culture?

Homely phrases like ‘it’s the way we do things around here’ or ‘it’s what people do when the boss isn’t around’ don’t help much. However, one word keeps cropping up when you delve into the research (presumably because it is the most obvious output of culture) and that word is behaviour.

Reflecting again on the seminar, I think it is reasonable to argue that behaviour is as integral to culture, as influence is to good leadership – in as much as it operates as a disciplining force. So if you think about it, being asked to lead a culture change leaves matters open to interpretation. Rephrasing the request to influence changes in behaviour brings much more focus. It sets out an obvious pair of questions for a start; what are the behaviours we see today and what would we like to see tomorrow?

Behaviours alone, however, are not enough. You still need clarity about the purpose of an organisation. Peter Drucker, the celebrated American management consultant, said of this purpose that: ‘Business is a process which converts a resource, distinct knowledge, into a contribution of economic value in the market place. The purpose of a business is to create a customer’.

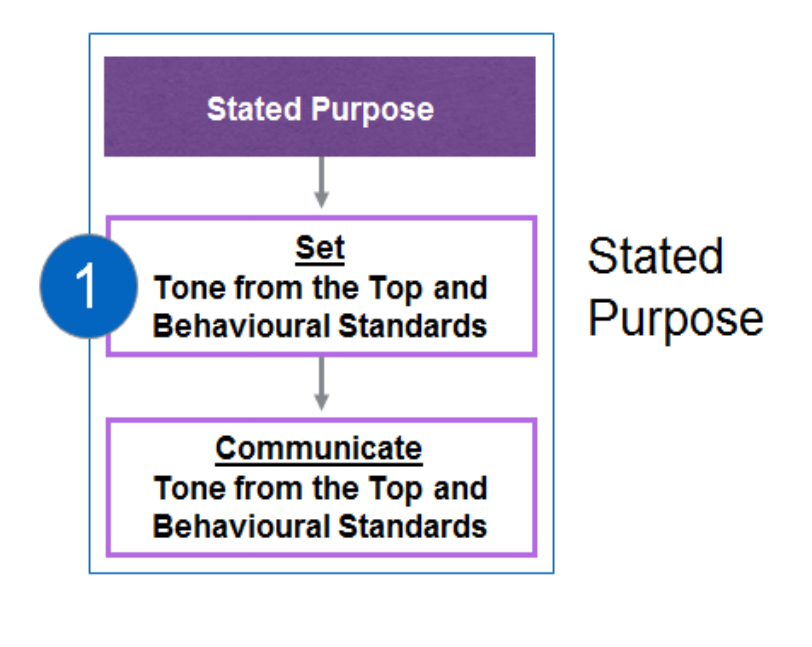

The board has to be clear about the firm’s purpose. I’m not going to get into a debate about how to clarify purpose because I want to concentrate on the impact purpose has on behaviour. I see there being a three stage process:

Stage 1

Two activities should follow the establishment by the board of the purpose of the organisation; setting out the needed behavioural standards (to deliver the stated purpose) and then communicating them. This is an essential part of the much-used phrase - ‘tone from the top’.

We seldom think though about how this phrase actually works. Additionally, you get pejorative derivatives like ‘the muttering from the middle’, with added spice when middle management (doing the muttering) are described as ‘permafrost’.

Permafrost and muttering are simply used by ‘the top’ when it hasn’t thought hard enough about how its ‘tone’ actually works. A form of scapegoating. It has always amazed me that middle management; the cadre who often carry an organisation and are essential to behaviour can be labelled ‘permafrost’, very often by their own senior leaders.

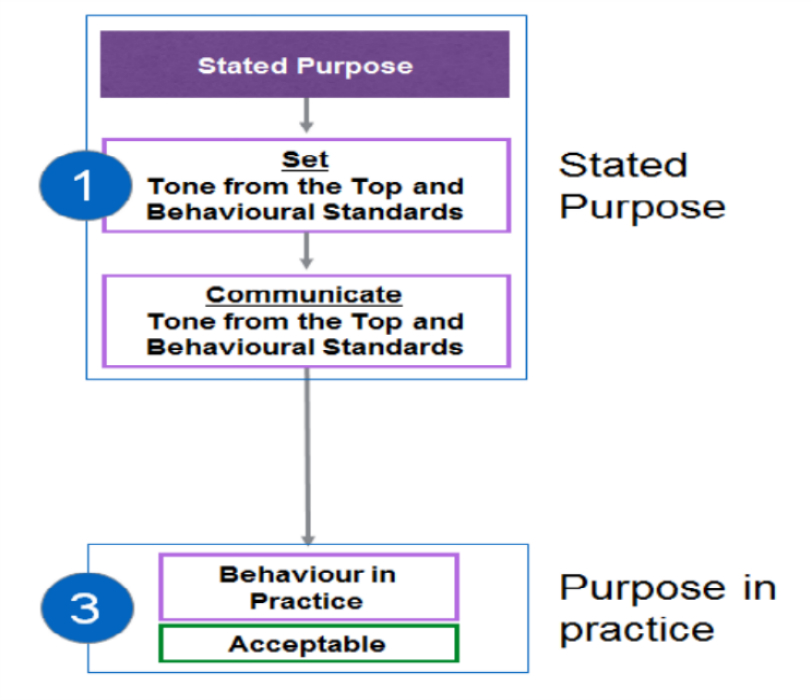

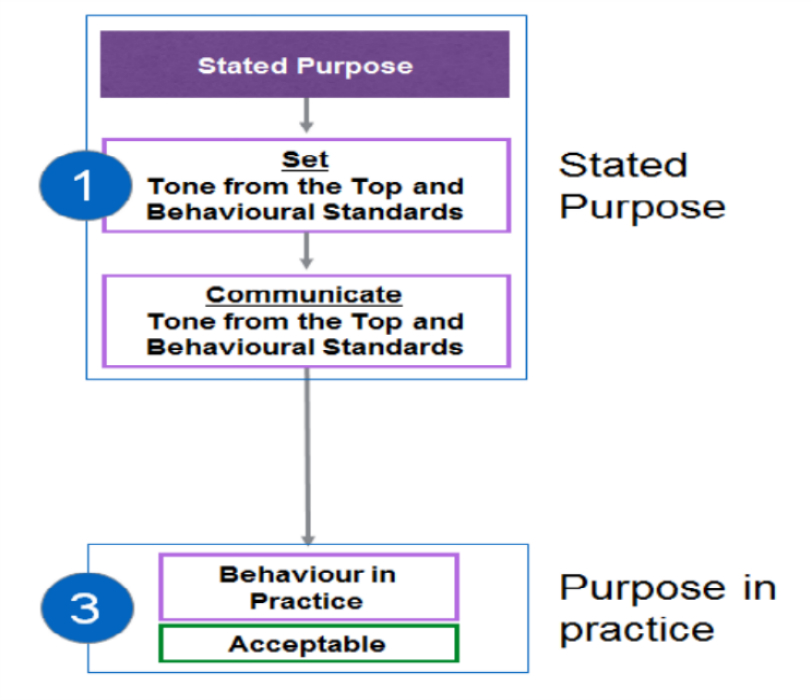

Where failure occurs, and the tone from the top doesn’t work, is in its communication. The additional and bigger error however is jumping straight from stage 1 to stage 3 as shown here:

Jump from stage 1 to 3

Stage 3 is what should happen in behavioural terms to achieve the stated purpose. Stage 3 is not the bottom of the organisation. The board and senior leadership of the firm must model behaviour - and therefore sit within it. But stage 1 is definitely the board and senior leadership. Only they can philosophise, analyse and decide on the stated purpose, and its communication falls to the CEO and other senior executives.

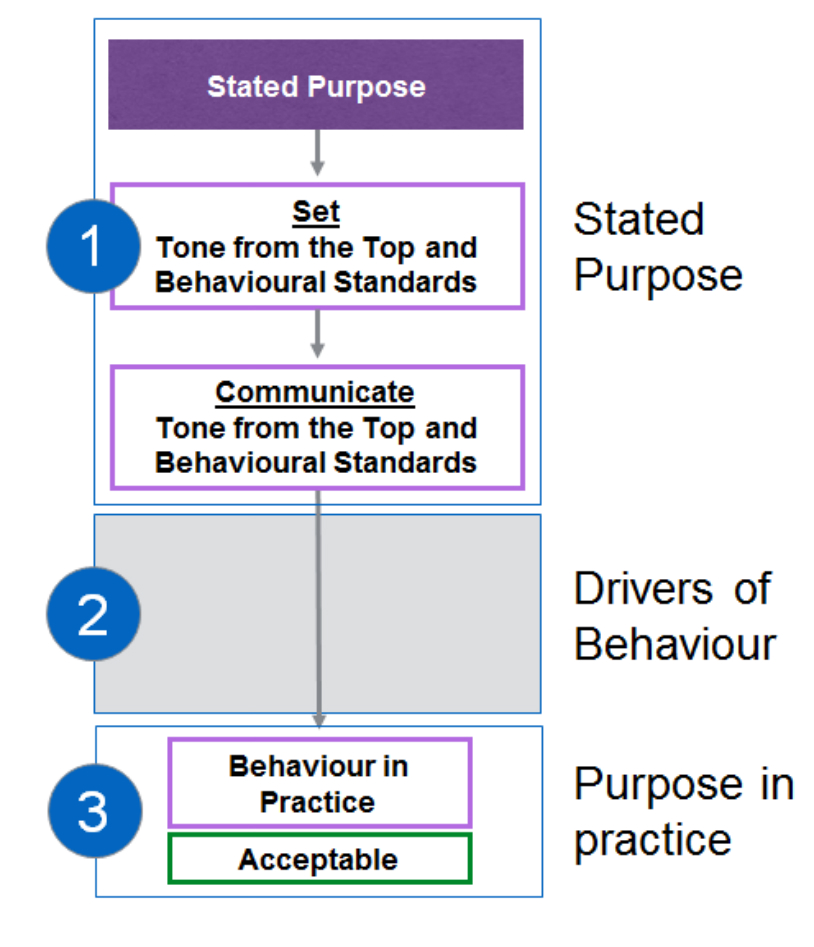

However, when instead of acceptable behaviours, the firm experiences unacceptable behaviours, it is very likely the missing component, stage 2, is the root cause of the problem.

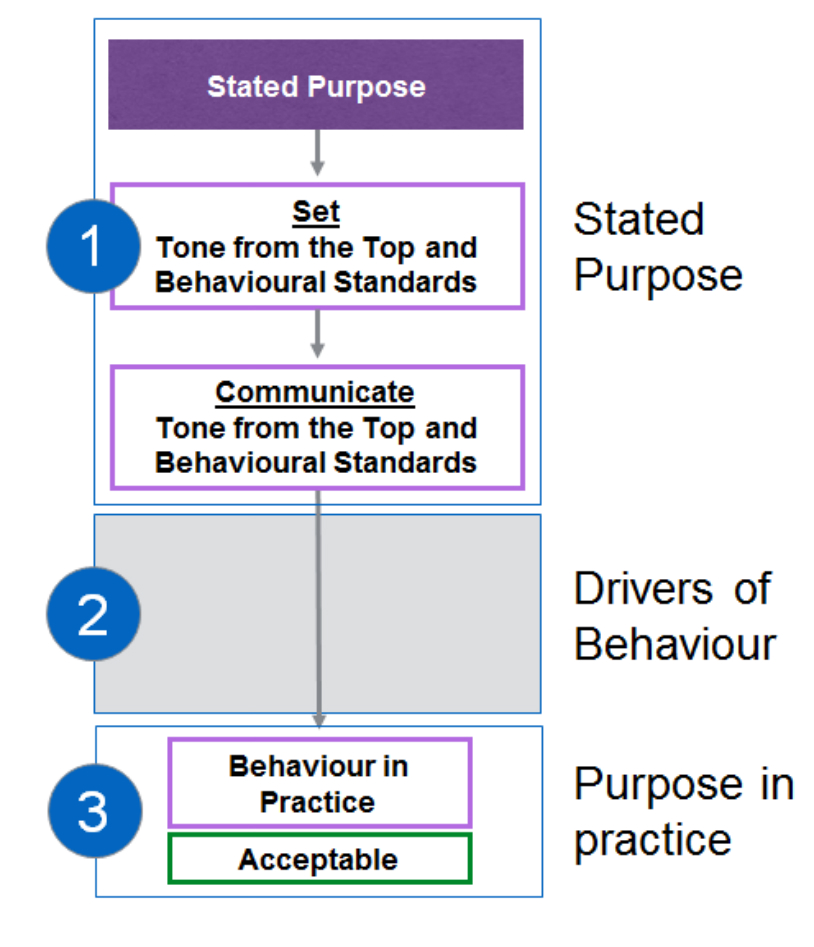

Sitting between a well communicated and thought through stated purpose and the purpose in practice are drivers of behaviour, these come in two forms, financial and non-financial. The great danger is that the drivers of behaviour are not understood, or if they are, not properly controlled. This misalignment is shown below:

The drivers of behaviour must be aligned with the stated purpose because the true test of tone from the top is behaviour. No matter how well defined and communicated the tone from the top is if behaviour is poor then so is the tone from the top.

Understanding and controlling the drivers of behaviour is intrinsically part of tone from the top. Misaligning stages 1 and 2 diverts behaviour away from what the ‘tone from the top’ says it wants. Thus, employees may well experience a beautifully thought through and communicated stage 1 - but if what drives them is outside this then don’t expect the tone from the top to be well reflected by behaviour on the ground.

There is a classic paper written over forty years ago which rejoices in the title; The Folly of Rewarding A, While Hoping For B. In a nutshell, if the tone from the top talks eloquently about B (customer need) but senior leaders reward A (Fee income) then expect fee income to grow and customer need to be paid lip service.

Senior leaders pressing for the delivery of outcomes that differ from the tone from the top damages trust inside the organisation. It cannot be surprising in these circumstances that internal and external employee surveys (such as the UK Banking Standards Board and www.glassdoor.com) will find employees saying things like;

- I do not always trust what our senior leaders say

- sometimes I have to trade ethics for business

- our strategy is unclear

The misalignment of behavioural drivers manifests itself not only in the wrong behaviours but also in trust being lost between senior leaders and the workforce.

In developing the idea of the three stage process and the importance of getting all stages aligned, a number of points logically follow. Stage 1 on its own will not deliver the required behaviours. You can’t get the required behaviours without it but the alignment of stage 2 with stage 1 is critical to success. This means alignment of purpose, communication and incentives, delivering this will build trust within the organisation. These three; trust, communication and incentives are key drivers of behaviour. I will add one more, that of decision making.

Culture forms and develops as people throughout the firm judge management on management’s judgements.

In watching the decisions made by the CEO and board, people throughout the organisation will look for two things; do decisions turn out well and if they don’t what happens? This is because people like working for winners but recognise that not all decisions do turn out well. But, if the decision that turns out in a disappointing way, or downright badly, is not owned by the decision maker and others carry the can, then this behaviour is seen for what it is and trust bites the dust.

The lack of responsibility assumed by senior people has been one of the enduring features of the 2007/8 bank failures. It is therefore no great leap to understand why popular trust in bankers has disappeared.

In reverse, behaviour impacts decision making by the way it guides decisions through past and present practice. It is the organisation’s experience of how it made past decisions that guide current and future decisions. For example, a firm with an historically strong low cost ethic will be making low cost decisions at levels throughout the firm. If the firm is successful in its industry because of its low cost approach to business, then low cost decisions will be celebrated. Now imagine the challenge of a change of strategy that moves away from low cost, let us say to innovation requiring a high and continual investment in R&D.

This is why change is so difficult. Change means new decisions have to fly in the face of how decisions were made in the past and what is perceived to be ‘the way we do things around here’. In short behaviours have to change. That which has previously guided the organisation on a day to day basis is suddenly in disarray, the guide has been lost.

The new culture, in the form of a new framework for making decisions which means behaving differently, has to be explained. “Why are we doing things differently?”, and “what is it I have to do differently?” Of course, no matter how well this is communicated if the drivers in stage 2 remain unchanged, old habits will die very hard.

My conclusion is there are four drivers of behaviour and all four need to be aligned if behaviour is to be what the board envisages will deliver the purpose of the organisation. The drivers are;

- Trust and trustworthiness

- Communications

- Decision making

- Incentives, financial and non-financial

Culture is a simpler concept if it is seen in terms of behaviour. The drivers of behaviour need to be understood and as far as possible overseen and controlled by boards.