The economic advantages of household credit products are well documented. Taking out loans allows people to smooth consumption over time, taking ownership of goods that they can pay back gradually, or to make long-term investments in the future.

But things can and do go wrong. Investments in the future don’t always succeed, and the best-laid repayment plans are disrupted by unexpected events. Debt can become unsustainable and people can become locked into hard-to-break cycles of taking expensive loans to meet short-term needs. In addition to the financial costs this entails, debt problems can lead to significant stress and anxiety.

Financial regulation often helps to reduce and mitigate these negative effects on wellbeing. But it has been difficult in the past to understand their magnitude and therefore to fully quantify the benefits of regulatory interventions.

A new piece of research, undertaken by consultants from Simetrica-Jacobs on behalf of the FCA, aims to make it easier to put a value on the adverse effects on wellbeing associated with certain types of debt and make such values useful in future policymaking.

How to put a value on the impact of debt on wellbeing

Empirical research on subjective wellbeing is a growing topic. It has been facilitated by a suite of questions now common in national surveys that typically ask people to rate their happiness, life satisfaction or other aspects of their wellbeing on a 0-10 scale. Recent FCA research on consumer financial wellbeing has exploited this type of data.

Building on these survey questions, the Simetrica-Jacobs report involved an approach known as the 3-stage wellbeing valuation method.

Stage 1 is to assess the effect on wellbeing of a product – in this case debt. Stage 2 involves placing a financial value on changes to wellbeing. Stage 3 involves combining the first two stages to produce a financial value for the wellbeing effect of debt.

Stage 1 makes use of the wellbeing questions in the Wealth and Assets Survey, carried out by the Office for National Statistics, to estimate the effect that entering debt has on ‘life-satisfaction’ as reported by respondents.

Importantly by following households over time the analysis took into account certain factors and life events that might have an effect on both debt and wellbeing (for example a wedding or a bereavement, as well as unobserved individual traits) and could create a bias in the findings. This is a substantial advance on previous studies. It also attempted to control for other changes in individuals’ overall financial situation, including as far as possible the assets that debt is usually used to acquire, in order to isolate the effects of debt from wider (and often positive) financial changes in their lives (for example housing assets).

Stage 2 makes use of existing work estimating the effect of exogenous increases in income (such as a small lottery win) on subjective wellbeing. This technique provides the benchmark - how much is a change in subjective wellbeing worth in monetary terms.

Stage 3 combines the first two stages - how much income would an individual need (stage 2) in order to cancel out the negative wellbeing associated with debt (stage 1). The research refers to this figure as the ‘compensating surplus’. This provides an estimate for the value in wellbeing terms of debt.

Crucially this technique was then applied to different types of debt to see how they might have a greater or lesser effect on wellbeing, and also to compare the wellbeing effects of specific events such as debt increasing or going into arrears.

The results

What types of debt or debt events have a significant effect on people’s subjective wellbeing?

Most strikingly, entering debt arrears is associated with strong negative effects on subjective wellbeing (a 0.36-point decrease in life satisfaction on the 0-10 scale). Although the absolute movement in life satisfaction sounds small, this is actually comparable in size to the effect of becoming unemployed estimated in previous research. Similarly, as an individual gets further behind on their debt and total arrears rise, wellbeing becomes statistically significantly lower.

Holding high-cost debt (for example overdrafts or payday loans) is also negatively associated with wellbeing, though the effect of a 1% increase in debt is smaller than a 1% increase in total arrears.

Personal context, understandably, also seems to determine the size of the wellbeing effect. For instance, the estimated negative wellbeing effects of arrears debt are greater if the affected individuals are also unemployed.

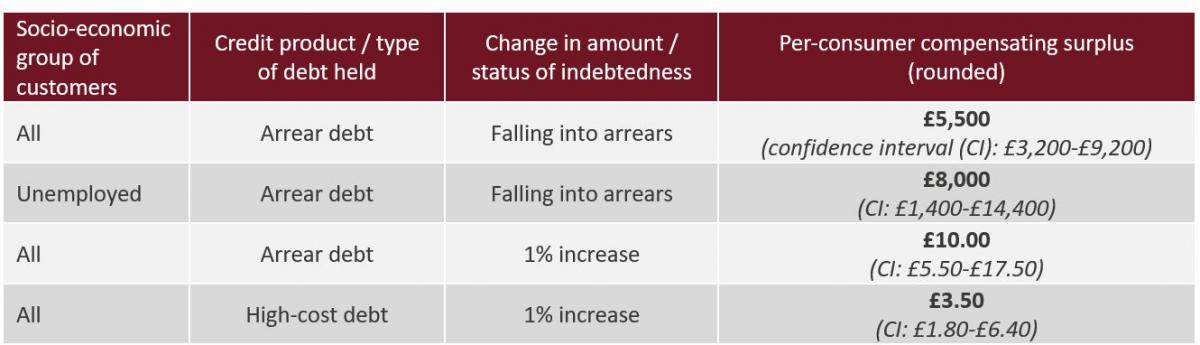

Using the three-stage valuation method on the statistically significant results, the report provides the following selected quantified monetary estimates of debt on wellbeing. The magnitude of the arrears result stands out in particular – the monetised estimate of someone falling into debt arrears is between £3,200 and £9,200.