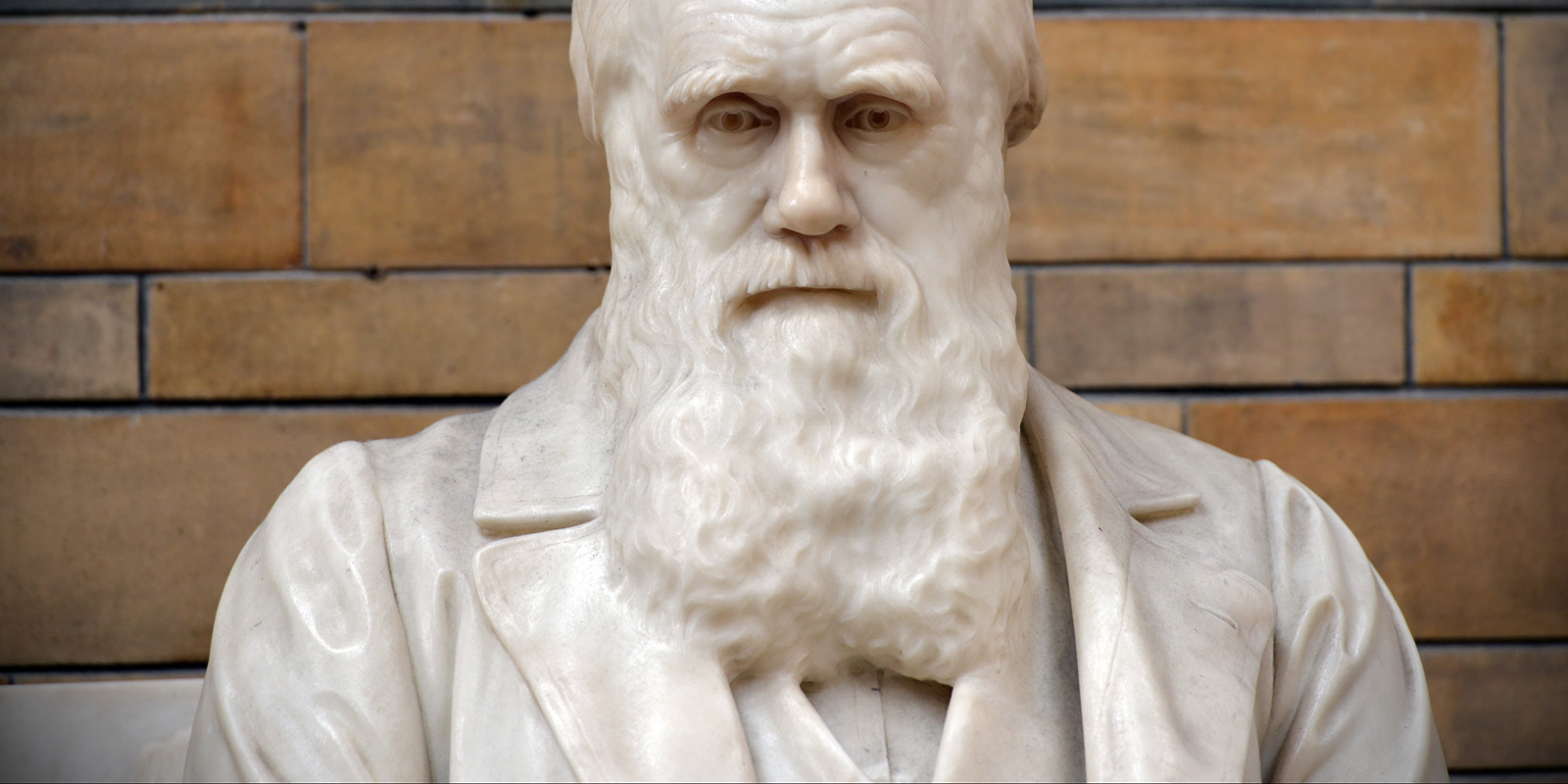

For example, doctors in Ancient Greece. We know for sure that price discrimination practices go as far back as Ancient Greece. The Swedish economist CH Lyttkens describes how medicine was practiced mainly by private doctors. They travelled between cities seeking demand for their services. There was no price regulation. With a local monopoly doctors were free to set their own prices. It appears that price discrimination was pervasive and in fact recommended in Hippocratic texts. Those with higher willingness to pay, the rich, were charged more. And the poor were charged much less. Interestingly, doctors advertised themselves as being charitable to the poor.

I will now set out our working definitions of price discrimination and cross-subsidy, give examples and some initial observations. Price discrimination occurs where firms charge prices to different consumer groups and have different mark-ups on the costs of supplying these groups. One example is where prices differ when the costs of supplying consumers are the same. So, this weekend, students will pay less to see the new James Bond film than most other people. But they will pay more than if they had gone to see it on a Wednesday.

An observation. Such price discrimination is seen as ‘normal’ and there are few calls for it to banned. Perhaps it is ‘legitimised’ by the low value of the individual contracts. Or necessary rationing when demand is high. Or the notion that it is ‘progressive’ to help the (presently) less well-off.

Another possible example is airlines offering different prices at different times or higher prices to groups than to individuals. (Late bookers and many groups have relatively few alternative offers.) Certainly it costs no more to fill a seat with a group member than with an individual.

Interestingly, there seem to be few calls for airline price discrimination to be banned. But what are the policy considerations here? No need to protect needless consumption? But late bookings may be true ‘distress purchases’. Perhaps generally they are not?

Here’s another example. My mother-in-law just bought an iPad, while I am a keen Microsoft Surface user. So I’m intrigued that US online travel agency, Orbitz, found that people who use Apple computers spend as much as 30% more per night on hotels. (Now, let’s be fair to Apple fans. I think in part the extra cash is for higher quality.) Anyway, as a result, Orbitz has started to show them different, costlier options than users of Windows computers see. Does it matter that Apple users are being charged more? And that this is because they revealed in another context that they are willing to pay more? Perhaps for higher quality, though many would argue otherwise! But I’ll stop. This is not a discussion about willingness to pay for brand. It follows from our definition of price discrimination that another form of it is when prices are uniform but costs of supply differ. For, in this case too, mark-ups must vary.

Cross-subsidy is often used to refer to the distributional consequences of price discrimination. Loosely speaking, consumers who are charged high mark-ups are thought to subsidise those who pay lower mark-ups.

But economists define cross-subsidy more narrowly, as cases where certain consumer groups or products have prices below cost.

Therefore cross-subsidy will occur in some, but by no means all, cases of price discrimination.

There is also a temporal version, where a single product or service is supplied below cost initially and then above cost in the future.

Examples of cross-subsidy are commonplace. For example, supermarkets commonly price basic goods such as milk or bread as ‘loss leaders’, to tempt consumers in and sell them more profitable items once they’ve entered. Or perhaps they cross-subsidise more simply by using special offers. Certainly, milk producers argue that prices are below cost.

The FCA’s market study on general insurance add-ons concluded that the point of sale advantage and limited information on availability and price of add-on insurance products led to the sale of poor value add-ons. These might well have been cross-subsidising sales of the main product. But we cannot say for sure that the main product is sold below cost, due to the problem of fixed and common costs in such financial services.

Some ‘Free if in credit’ accounts must involve below cost pricing, regardless of the fixed and common costs problem. For example where balances are low and there is no card usage to generate interchange fees. However cases are fewer than first appears. Not only do lots of account users incur charges. Many also forego non-trivial interest. And generate significant interchange fees. Also, in expectation, all accounts may yield revenues above costs. It will be interesting to see whether Big Data leads to discrimination in offers of ‘Free if in credit’ accounts.

I mentioned that price discrimination may involve cross-subsidy. The recent FCA market study on cash savings found that interest rates on accounts held with the same provider for years were lower than on newer accounts. This could be price discrimination as we found no compelling evidence to support the view that these lower interest rates are due to higher costs of supplying older accounts. And the back-book might economically cross-subsidise the front-book where high interest paid plus operating costs could exceed revenues derived from balances. But we don’t know for sure, given fixed and common costs. (‘Stickier’, back-book deposits may also help firms meet prudential liquidity requirements.)

I’ve said that my definitions are simpler than the real world, where complex definitions provide what compliance consultants call ‘regulatory opportunities’! But this does not mean there is nothing important about them. Far from it. These are economists’ definitions of the concepts. They help us assess the efficiency of markets. For sure, efficiency is not the sole concern of policy makers, but it does determine what is available for distribution. Meaning determine what can be distributed among all groups of market participants about whom public policy may be concerned.

So, are price discrimination and cross-subsidy increasing trends in financial services?

Notwithstanding at least 2500 years of price discrimination, advances in technology and computing are likely to increase firms’ ability to price discriminate and cross-subsidise.

Financial services firms often hold substantial amounts of information about their customers. This can be used to segment them into different groups according to their propensity to switch suppliers. Or according to their price sensitivity to the charges levied by an individual firm.

Specifically, ‘Big Data’, meaning increased availability of deep, long and wide consumer and other data and better analytics, will help firms discriminate. For example, in insurance it already raises interesting issues about risk pooling and pricing.

Clearly then, price discrimination and cross-subsidy are relevant to the FCA and the 2015/16 Business Plan includes a study of Big Data. The scope of this is not yet decided.

Now let’s take stock. I have:

- Defined price discrimination and cross-subsidy.

- Set them in the context of dynamic markets and today’s technology.

- Set them in their historical context.

- Given some examples.

I trust these four points provide sufficient context. To sum up from a policy and economics perspective:

Price discrimination and cross-subsidy would not occur in textbook “perfect competition” markets. So they may prompt official intervention. But public concerns are often different, reflecting notions of fairness and unfairness. Thus there seems to be little concern about the Gender Directive leading to uniform motor insurance prices apparently settling nearer the male average than the weighted average. And, some economically non-discriminatory prices such as those for pensioners’ travel insurance and genetically determined medical insurance are often seen as problematic.

Thus competition authorities need to use economics objectively to set policy here. Economics can reveal relevant market dynamics to show where price discrimination and cross-subsidy help consumers and where they don’t. And provides evidence about designing interventions. And what the true costs and benefits of interventions would be.

So why exactly might the FCA care about price discrimination and cross-subsidy? Including to protect what’s good about them?

But first, let’s stand back and think for a moment. There is a potentially dangerous asymmetry in the job description of many regulators. Historically, we have been expected to stop bad stuff happening but not necessarily to make good things happen. In the extreme, this could limit the benefits of regulation mostly to ones arising from improving current equilibria in markets. And the far greater potential gains from ‘positive’ regulation shifting markets to fresh equilibria would not often be reaped.

So in the past we have tended to identify problems (adverse events) and then intervened to deal with them. And, naturally, smart regulators have tried to get ahead of the game by also identifying ‘risks’. Bad things that might happen. And do something about them too.

But the FCA, thanks to statute, is different from almost all financial regulators in history. Today we have the competition objective. To ‘make markets work well’. This is an excellent change. This is ‘positive’ not ‘negative’ regulation, and its benefits may be very large indeed.

Now the distinction just made really matters in the case of price discrimination and cross-subsidy. They need to be approached in a ‘positive’ mind-set rather than the traditional ‘negative’ one because we must be open to the possibility, case-by-case, that they are socially beneficial.

So, before turning to any potential issues or concerns with them, it is important to highlight the many positives that they have for both consumers and firms. If we are clear about the benefits, we can protect or enhance them in any intervention that is on balance warranted.

Here again we can turn to the example of student discount on cinema tickets. In this case of price discrimination, the students benefit from lower prices. This is relative to the higher uniform price that they would have paid were there no price discrimination. Which also brings extra revenue to firms because some cash-poor students would not go to the cinema if forced to pay full price. Similarly, consumers who pop into the supermarket for a pint of milk and resist that cross-subsidising chocolate bar at the till benefit from just buying the cross-subsidised milk. What’s not to like?

In financial services too, price discrimination and cross-subsidisation may bring benefits to consumers and firms. Those consumers who do not go overdrawn may benefit from low cost banking. Those who didn’t buy PPI may benefit from cheaper loans. Those who shop around for their car or home insurance will pay less than those who do not.

An aside. The Competition and Market Authority’s October 2015 remedies notice on banking includes an important observation. Namely, that the benefits of the free-if-in-credit model for personal current accounts appear not to come at the cost of reduced competition. According to a comparison with switching rates in non-free-if-in-credit countries and non-free-if-in-credit UK banking markets.

Some of the examples already discussed demonstrate that price discrimination and cross-subsidy can increase consumption. Which is typically good for consumers. They may also increase firms’ profits. Which is good for the stakeholders in firms, who of course include shareholders. Such as the funds we hope will pay our pensions.

However, turning now to why we might care about price discrimination, let’s consider two contrasting, highly stylised examples. These are designed to allow clear inferences to be drawn and are not necessarily realistic.

First, a firm charging a uniform price to all customers identifies a group of consumers that is currently unserved. It then charges a lower price (but still above economic cost) to those customers while keeping its price to existing customers the same. Some new customers are served and thus gain. And the firm gains additional profits from selling to these new customers. There are no losers because existing customers still pay the same price. Price discrimination is unambiguously a good thing in this situation relative to the firm charging a single price.

Second, a firm identifies a group of existing consumers to which it can profitably offer a higher price. But it keeps the price the same to its other existing consumers. Some of the existing consumers charged a higher price will stop buying or buy less, so are worse off. The other existing customers who continue to buy the same amount lose through paying a higher price. The other consumers continue to face the pre-existing price, so no consumers gain. In this stylised example the customer base is finite so there’s no advantage to offering a lower price to attract more customers. The firm makes additional profits as price increase outweighs volume fall. Price discrimination here is unambiguously a bad thing for consumers. But it’s nice for the shareholders, if governance is sound.

These are two extreme cases, with clear cut results. Typically there will be winners and losers within the consumer group. The general insight from economic analysis is that the losers will outweigh the gainers unless overall output and consumption increases as a result of price discrimination. This needs to be kept in mind because sometimes the policy choice will be a trade-off between lower ‘unfairness’ and lower total consumer welfare.

OK, let’s take stock again. We have just seen that price discrimination and cross-subsidy can generate a range of costs and benefits. Or, in the case of pure transfers, a range of winners and losers.

Now let’s consider some specific policy concerns.

1. The savvy may benefit from the unsavvy who may merit protection.

Or as we might say: a fundamental story about human nature. Let’s take, for example, Aesop’s fable about the lazy grasshopper and the hard-working ants. The grasshopper ignores and the ants vigorously anticipate the problem of acquiring sufficient winter supplies. For present purposes we might regard the ants as the savvy consumers in the well-known model by Armstrong and Vickers. The model I’m talking about is of competition in a market with hard-to-determine charges after point-of-sale. I’ll call them ‘later’ prices. And let’s say that the grasshopper represents the non-savvy consumers in this model.

Now, as Aesop goes on to describe, when winter came the grasshopper suffered badly for not being savvy in the summer. The later price of inattention was pretty high. Unfortunately, unlike Armstrong and Vickers, Aesop does not tell us what happens in the market for winter supplies when the ratio of ants to grasshoppers changes. Nor does he tell us the implications of different levels of the high ‘later’ price faced by the unsavvy grasshoppers.

I’d like to think, though, that the story would have been consistent with the model: that somehow having lots of savvy ants in the society of the mini-beasts would have helped the grasshoppers. Perhaps because winter supplies would be cheaply available due to intense production by the ants. Unless, of course, the ‘later’ prices were really high and handed a big cross-subsidy to the ants. Perhaps because the grasshopper would pay anything when hungry.

Anyway, here are two take-aways from this fable (and especially from Armstrong and Vickers):

- costs and benefits of price discrimination and cross-subsidy really depend on the market’s details

- savvy consumers may help, OR profit from, the unsavvy.

Finally, on this, should the regulator care about the happy-go-lucky grasshoppers? Is the grasshopper showing a ‘behavioural bias’, for example myopia, that somehow merits our concern? Or is the grasshopper just a person with a very high discount rate?

2. Front-book and back-book (which is mostly an application of savvy and unsavvy)

The old saw ‘don’t judge a book just by the cover’ makes a good point for us. That people led in by an attractive front book offer may find the rest of the book far less attractive. This could be exploitative where vulnerable or captive consumer groups are charged very high prices because of their inability or reluctance to switch away.

In a number of financial services markets, firms offer introductory deals. This may be explicit e.g. a bonus interest rate for a fixed period. Or implicit, e.g. lower prices for new insurance customers. From a firm’s perspective, observing a consumer’s behaviour once the introductory period ends is a useful screening device. It allows the firm to assess whether the consumer is ‘savvy’ and switches after the end of the introductory period. Or ‘non-savvy’ and stays with the product after the expiry of the introductory offer. Firms use this information by charging higher prices to ‘non-savvy’ consumers, allowing them to offer prices or interest rates attractive to active consumers looking for a good deal.

The FCA’s recent market study on cash savings, for example, showed that providers of cash saving products use pricing strategies consistent with such ‘screening’. Providers often had a wide range of products on their books as new products were frequently introduced, for example offering bonus rates to new customers. This is the front-book. And older products were withdrawn from sale or no longer marketed to new customers.

The terms of older products may be progressively worsened, leading to extremely differentiated pricing: the non-switching, non-negotiating back-book customers pay far more than the front-book. We understand that householders who have not switched their insurance provider for 15 years may pay three times more than recent switchers. And many of the non-switchers are old and vulnerable. Is this acceptable? How could it be fair?

Also, firms are unlikely to lower prices sufficiently to offset high, back-book returns. This is to avoid attracting really price-sensitive customers who are unlikely ever to convert to the back-book. On the economic efficiency downside, this means firms could make above-normal returns. So we might focus on markets where concentration will stop such returns being competed away. On the upside, inefficient consumption of the low-priced service (by those unwilling to pay its marginal cost) is reduced.

3. Contingent charges and complexity

Suppose this poor person just started reading the terms and conditions of their current account. Or, given we are talking about economics, let’s say our happy online shopper is trying to unshroud the attributes of a product as described in the model of Gabaix and Laibson.

So, on the one hand, she is too late. Where a fraction of consumers are unaware of the add-on or subsequent price (e.g. contingent charge) there is an incentive to increase the price of the add-on. So people who are poor at unshrouding may cross-subsidise those who are good at it.

On the other hand, in a competitive market, the overall price of the bundle will be driven to cost. The up-front price is reduced by the high-priced add-on (subject to the point above about incentives not to lower prices sufficiently to offset high, back-book returns). A policy view of the bundle being priced near cost will depend in part on the ratio of those buying the main product only to those buying the bundle, and on the composition of these two groups.

Again, therefore, the model tells us that policy makers need to understand relevant competition. Some consumers are better than others at dealing with complexity. Price discrimination may be used to increase complexity and harm competition.

Web-based retail finance is growing fast. So it’s worth noting that there is enormous scope for unshrouding complexity online. As the photo of the ‘iTunes scroll’ in Ben-Shahar and Schneider’s book on failures of mandated disclosure shows.

In fact, a series of studies by Marotta-Wurgler and co-authors shows that 99.8% of online buyers of software products tick terms and conditions without reading them. They also find that firms have been increasing the length of their contract terms over the past ten years, often changing them materially. Given what I have just described, it is perhaps no surprise that these contract changes typically favour sellers.

I could ask, but won’t, how many in the audience – or others reading this - have read the terms and conditions of their personal current account or ISA? And how often have you been notified of changes to them? And how often did you challenge the changes? Or even read them?

4. Competition concerns

In almost all real-world markets, one or more firms will have some market power. They may use it to price discriminate. This in turn may give rise to specific competition concerns. And here’s an example.

Predatory pricing - attempting to force a rival out of the market. Though probably not common, it could happen through price discrimination such as charging a low price to price-sensitive consumers in certain segments. Or through cross-subsidisation between products with some prices set below cost.

Secondly, cross-subsidy may enable foreclosure, preventing entry and reducing competition. In principle—though we have no specific evidence—this could happen where a back-book cross-subsidises a front book, and consumers believe they are smart enough to get and keep getting the subsidised front book price. In this case, a typical entrant lacking a back-book cannot match the front book rate or price because this would not cover its costs. And no consumers will pick the sustainable long term rate or price (the weighted average of the front and back-book prices or rates) that the entrant can offer.

Thus a possible entrant with just a small improvement on current efficiency is unlikely to enter in practice. Of course a step-change innovator may be able to enter, and in some markets incumbents might have cost disadvantages. Reduced entry matters if new firms would offer increased variety or a superior price/quality combination or improved suitability, relative to demand.

Obviously, there may be distributional concerns from the implied subsidy from one consumer group to another consumer group.

Let’s take stock again.

- So far we have learned what price discrimination and cross-subsidy are.

- That they have a long history, are commonplace, and are becoming more common, including in financial services.

- And that they can have benefits and/or raise important policy concerns.

Next a few observations about assessing whether regulatory intervention is warranted: it is not always obvious.

Let’s take a topical example. The Kardashian Kard, which I must confess is not especially close to my heart, or my wallet. It is a prepaid debit card available in the USA that has pictures of reality TV stars the Kardashians on the front. It is virtually identical to other prepaid debit cards, with one notable exception – the fees.

Slate Magazine has a run-down of these. For a six-month card customers pay $60 up-front. It’s $100 for 12 months. (The median fee for similar products is $10.) After those six or 12 months, the monthly fee is $8. Users pay $1.50 to withdraw cash at an ATM and $1 to check their balance. And $1.50 to speak with a customer service representative. If they lose their card, a replacement is $10. Cancellation is $6.

Someone using the card for $200 of monthly spend could easily pay $80 in fees, whereas rivals would charge between nothing and $36.

What should be the attitude of policy makers towards the Kardashian Kard? Do we say we don’t care as most of the buyers will be rather well-off and less focused on value for money than on the Kardashians’ latest exploits - Kourtney has left Scott and Kim is pregnant again (or so I’m told)? And anyway isn’t it the buyers’ fault they are unaware of cheaper cards onto which any picture, even of themselves, can be printed?

Or do we worry that at the margin some poor parents will find themselves under siege from their offspring? Offspring who themselves are struggling with social pressure from Kardashian Kard–rich peers? I personally doubt it but recognise that once we leave the safe harbour of efficiency considerations a wide range of views will be encountered.

Anyway, where an intervention may be warranted, what sort of analysis would help us consider what to do? Given that price discrimination or cross-subsidy may be good or bad, a number of factors could be considered initially when debating possible intervention, for example:

- The strength of each firm’s position in the market.

- Analysis of costs to assess the prices being charged and their likely impacts – but this is often very hard e.g. in cross-subsidy.

- Whether the observed pricing excludes competitors.

- Whether there is localised market power that consumers could be helped to avoid.

- Whether a large number or share of consumers who pay a high price, or are excluded from buying a product or service, are ‘vulnerable’, for example due to having few alternatives, particular physical or mental health difficulties or being financially-distressed.

Sometimes consideration of these issues is unnecessary, for example cost analysis when simple negotiation leads to a huge cut in an autorenewal price. Or it could be highly informative, revealing a clear issue to address. In reality, though, the position may be complex and evolving. Thus observation of price discrimination and initial analysis of it might best result in a candidate for a market investigation of what is driving the cost-price relationships, etc.

When examining the merits of intervening, a regulator must consider its objectives as well as its statutory powers. The FCA has the strategic objective of ensuring that financial services markets function well. And three operational objectives: consumer protection, market integrity, and competition. I will briefly comment on the competition objective.

An important point here is that the FCA’s competition objective is not about any competition. It is about competition in the interests of consumers. So any conflicts between the competition duty and other objectives should be rare. A market that ‘works well’ will be competitive, have integrity and deliver the outcomes that consumers demand. Equally, the competitive price to insure high-risk, vulnerable consumers may be very high.

All is indeed not straightforward. An intervention to restrict price discrimination practices (such as firms taking savings products off-sale and reducing interest rates) may protect those consumers who are least engaged. However price harmonisation reduces consumers’ incentives to switch and therefore firms’ incentives to compete. In some markets this could penalise poor consumers who take the trouble to shop around.

Before discussing types of intervention, I will consider some difficulties in measuring their impacts.

Assessing the merits of proposed interventions is hard. So here are some words of caution. For example, what measurements can meaningfully trade off the interests of different parties such as the typical Kardashian Kard buyer and the marginal Kardashian Kard buyer?

Cost-benefit analysis of policy should compare social welfare under the status quo with social welfare under the proposed intervention. But measuring this change or social welfare at all is extremely challenging. How can policy makers know consumers’ true valuations under all relevant states?

And cross-subsidy involves transfers from one group of consumers to another. Should we rate them all the same? In which case a transfer does not matter. Still, how can we attach meaningful and appropriate welfare weights to different groups? Should we rely on findings that higher income earners only receive half the utility from an additional pound of income that lower earners do? Perhaps referencing “progressive” income taxation?

In practice it is hard to make a scientific valuation of welfare weights. And much economic analysis faces the challenge of ‘incredible certitude’, as explained by Charles Manski, who for example shows that apparent clarity often depends on unjustifiably strong assumptions.

Moreover, already-very-tricky welfare measurement became more challenging for policy makers as Behavioural Economics led to behavioural welfare analysis (assessing true preferences and valuations when biases and errors are present) as described by Bernheim and Rangel and others.

A possible alternative – stated or inferred well-being – is sometimes used, as in the FSA’s Mortgage Market Review and the FCA’s Pay Day Lending Cap analysis. But there is still some unavoidable uncertainty. The researcher is partly reliant on consumers’ statements about abstract questions, though cross-referencing to objective facts helps. And framing biases arise even in well-deigned surveys. The unit of account is also tricky: how to monetise the results, since well-being analysis lacks the ‘willingness to pay’ monetary metric of welfare analysis.

Some argue that neuroeconomics offers a scientific method of determining weights by helping identify the underlying causes of individual economic behaviour and intensity of preferences. Every human action is rooted in the brain so examining which areas of the brain light up when people are offered certain choices or undertake certain actions could yield information on people’s preferences. However, we are still some considerable distance from this happy state.

At our last stock-take, we had defined price discrimination and cross-subsidy, looked at their history and considered their benefits and the policy concerns they raise. Since then we have discussed the difficulty of deciding whether to intervene and of measuring any interventions. Now we are going to discuss the merits of different interventions.

Least ‘interventionist’ are informational and education remedies. These may help consumers identify and mitigate harmful price discrimination. An example is the FCA’s cash savings market study. This proposed highlighting to consumers the benefits of shopping around for cash savings products.

The benefits of this approach are that it may promote effective competition. It is the least likely to cause unintended consequences, although customers getting low prices may now face higher prices if others start to shop around more. A drawback is the difficulty of determining how best information should be formatted and disclosed in real-world markets. Another problem is that in the real world standard and behaviourally-informed disclosures may increasingly be undermined by other strategic disclosures or framing or behaviour by firms.

More interventionist is action at point of sale e.g. to regulate how products are sold. This may include banning the sale of add-ons at the point of a main sale, as has been done by UK competition authorities. The deferred opt-in for Guaranteed Asset Protection Insurance is a related example of altering the choice architecture. The expectation is that fewer people will buy something they don’t ‘really’ want.

Contingent pricing also fits here. For example, prior to the CARD Act the default was that, if you exceeded your credit card limit, the card company would decide whether or not to honour the transaction. If it allowed the transaction, it would charge you an overlimit fee. Now, unless the consumer explicitly opts-in to this contingent fee, it can’t be charged. Very few people do opt-in. But firms seem not to refuse many transactions. They typically just increase the credit limit. Did they increase other prices, relative to the correct counterfactual?

The advantage of these approaches is that their effect depends less on consumer action. But there is a risk of reduced consumer choice. And unintended consequences such as inefficient uptake or usage of financial services.

Finally, highly interventionist measures include prohibition of price discrimination or of below-cost pricing, as well as price capping… A direct solution to a problematic case of price discrimination is price capping. But it has considerable drawbacks too. Pricing practices take many different forms and evolve dynamically over time as part of the competitive process. Any attempt to set or cap prices inevitably restricts this.

For example, setting or capping prices creates disincentives for provision of non-price elements of the product, and so may lead to a lower level or quality of service.

Furthermore, capping or setting prices can lead to reduced access for consumers because the price does not cover their (expected) cost or risk.

There are also practical problems. Determining a welfare-enhancing level of cap requires the regulator to have substantial information which may be unavailable or very resource-intensive to obtain. Then there is the problem of welfare weights. And where information about welfare cannot be found, the available proxies have significant weaknesses.

Direct price regulation might only be a desirable option if:

- there is a clearly identified and severe problem; and

- all other efforts to stimulate competition or provide an appropriate degree of consumer protection have proved ineffective; and

- the market is relatively stable and predictable in how it will develop; and

- the regulator is able to obtain enough information to set appropriate limits on prices.

One might expect such a combination of circumstances to be rare.

The FCA did impose a price cap in the high-cost, short-term credit (‘payday lending’) market, due to legal requirements. It was clear that this would terminate supply to certain consumers but also that loss of access was beneficial in preventing consumer harm: the interest rate was eye-wateringly high and firms lent so irresponsibly that 60% of first-time borrowers defaulted, incurring massive charges and damage to their credit record.

At last, the conclusion

We started by setting price discrimination and cross-subsidy in their historical and market context. We defined them. We discussed their benefits, possible growth and when they might concern financial services regulators. We distinguished economic concerns from fairness concerns. We also saw that the case for intervention may be unclear. And that remedy design is challenging. And that reliable measurement of the impacts of intervention is more challenging still.

An important issue we have discussed is that careful observation of what’s going on in a market really matters in cases of price discrimination and cross-subsidy. For we have seen that price discrimination and cross-subsidy may be both efficient and generate outcomes that are widely regarded as socially desirable. We have also seen that they can produce outcomes whose desirability is genuinely open to debate, even if efficient. And sometimes they produce outcomes which most reasonable people would consider deeply unfair or a potential obstacle to effective competition.

So I conclude by saying that a sensible financial regulator will care about price discrimination and cross-subsidy, will consider it important to look very closely at individual cases, and only then determine the appropriate response, if any.

Thank you for your attention.